Menu

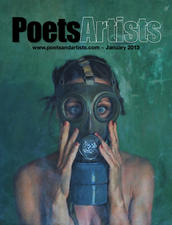

(Poets & Artists, Issue #42, January 2013)

HOMELAND

When did you turn into such an American?

Mother asks when I return

for my annual summer pilgrimage.

A baby goat lays slaughtered in my honor

by the old stone and mud house

in the mountains

where houses cling to the steep slopes

like some wretched crows

in the branches of the old walnut tree

under which we ate lunch in the summers

when my grandfather put down the hoe

and my uncle came back with the goats.

Back when I climbed the walnut tree

and swung off its branches

and didn’t mind the outhouse

up the narrow path

where instead of toilet paper

old newspapers hung on a rusty nail.

Back when I helped Grandma bake bread

in the woodstove,

and in school

I wore the red Young Pioneers scarf.

Back when I hadn’t even heard

of the skyscrapers and highways

in that place far away

that will bewitch me years later

from the small black and white screen

that Mother covered with an embroidered cloth

to keep the dust away.

The walnut tree has long dried out

and my grandparents’ hands

are brown and knotted

like its roots,

and the house smells of rot

and old Communist books.

The outhouse buzzes with flies

and I am upset

about a dead baby goat.

Guilt greases my fingers

when I try to eat it.

When did I turn into such an American?

I bring presents,

cheap stuff from Chinatown

a wristwatch for Grandpa and

a fake Armani shirt for my uncle,

who’s back with the goats,

and I’m ashamed

because he thinks its real.

I tightrope walk

between two continents

and the sea in between

only grows wider

and I no longer know

where home is.

I worked hard in America.

I cleaned Fifth Avenue apartments

whose owners forgot to pay me,

and at night, at the 92 Street Y,

I studied English

across from a Swedish au pair

and a Russian PhD historian.

I learned to do small talk

and smile at strangers.

But I will always be the girl at the party

everyone asks: “Where you from?”

Back where I am from,

the cafés are choked in cigarette smoke

and along the highways

girls stand in miniskirts

like spring flowers

sprouting from the trash.

And my old friends

who used to gather in the city squares

shouting, “Down with the Reds,

we want democracy,”

flaunt their latest model cell phones.

And my uncle says

he wants to be buried

in his Armani shirt.

COMRADE GOD

I grew up fearless of you.

Free of you. Empty of you.

You, my schoolbook said,

were nothing but an invention

to keep the masses at bay.

In New York City decades later

under a crescent moon unmoved

aches unarticulated

dreams undone

I gaze into a neon void

and whisper your name.

Fear has many faces

and the honey voice of copper

(mine tastes of cigarettes and semi-dark chocolate).

I abandon myself to oblivion.

I gorge on stupor sprinkled with nothingness.

But I long to believe

and belief is what I ask for:

Comrade God,

please give me faith.

AFTER THE WALL

Skinheads

Junkies

Mafia

Children in rags

beg on the streets

Old people with canes

dig into garbage bins

Hookers in miniskirts grow

like weeds

by the roads

outside the cities.

McDonalds

Dunkin Donuts

Starbucks—

we’ve got it all.

Freedom, says the crow,

perched on the shoulder of the beheaded Lenin’s statue,

is plain old Capitalism

cloaked in the robes of Democracy.

Because there was no God

and there was no competition

and no motivation to work

because Money was Evil

and the Party was King

because they pretended to pay us

and we pretended to work

because we were all equal

—equally terrified of Durzhavna Sigurnost

because we hunted Levi’s jeans

and fought at grocery stores for bananas

and there was something about Freedom of Speech

and Free Market

but I was just a kid

standing guard by Brezhnev’s bust in school

hand raised, thumb folded,

the Young Pioneer’s scarf flaming around my neck

(Chaffin Journal, 2010)

Communism Remembered

Snow gathers

on the gray coats of people,

lining in front of the store

for more than two blocks.

People who’d left work

because they’d heard

there were bananas

in the grocery on Zhdanov Street.

I stand guard

by Brezhnev’s bust

in my Young Pioneers uniform

that gray November day he died.

Chernobyl cherries taste just

like any other cherries.

The Communist government

forgot to tell us about

the disaster and the danger

of eating the fruits

that fed on the Chernobyl rains.

My neighbor lays dead,

shot in the chest

only 23 years old, a teacher

whose boyfriend shot her

but didn’t spent a day behind bars

because his father

was in the Communist Echelon.

We are all in the kitchen,

cuddled around the kerosene stove,

my uncle sitting with his ear glued to the radio

from where The Voice of America

comes and goes out of tune.

Copyright 2024 © DanielaPetrova.com All Rights Reserved

Menu